Home

🛠 The desktop version is currently under construction.

Please use a tablet.

📱 This site is soon available on small screens.

Please use a tablet.

Bernadette Mayer places a stone on her forehead as paperweight, trying to keep her thoughts from flying away. She moves on to become the stone itself. Mayer was a poet associated with the New York School of the 1960s.

She once said: “The first big influence on my writing was The Scarlett Letter. Next came the Steins: Gertrude, Albert, and Wittgenstein. If there is a book by a philosopher about language, you better read his: Here’s a little poem from him: Look at a stone and imagine it having sensations [...] i turn to stone and my pain goes on”

As rose is rose and stone is stein which in portuguese is „pedra“. Adélia Prado, a brazilian poet, writes in her poem passion: „At times, god empties me from poetry. I look at stone and see simply stone.“

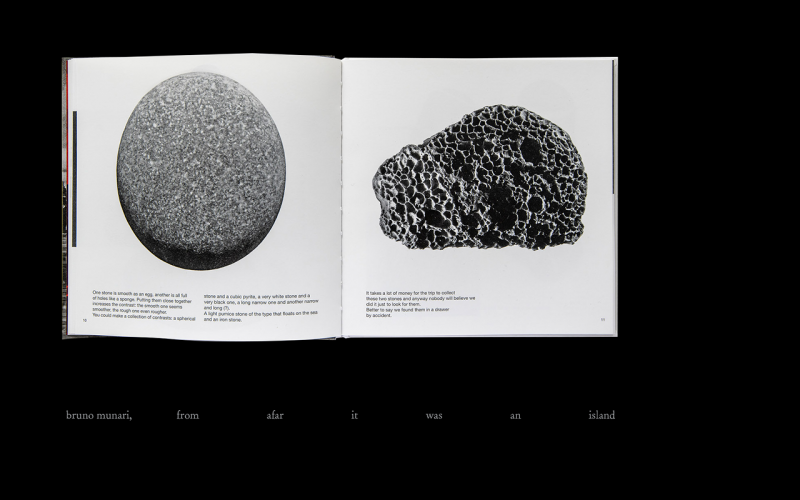

Bruno Munari also looked at stone and he wrote a whole book on how each of them is a universe and he called it from afar it was an island. Munari was an italian designer and as designers like tell long stories about simple things it’s often you hear people say that design starts when the first cavemans built their first tools, but rather design marks the X where the roles of conceptualizing and creating are first divided to generate capital.

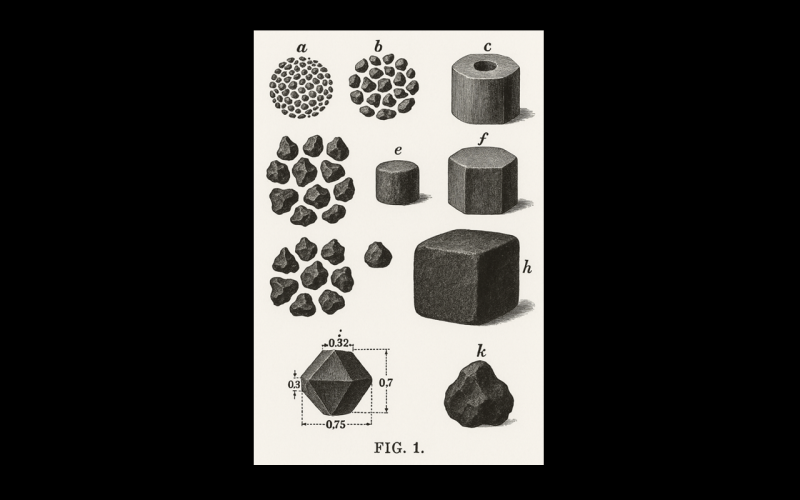

The industrial revolution, of course, played a major role in world war one. New military machinery could be produced at a much larger scale and at a much faster rate than ever before. It was the biggest leap in warfare technology since the invention of gunpowder in the 9th century.

Stoning is explicitly mentioned in the bible around 20 times, depending on the translation. More notably, in the stoning of Stephen, the first christian martyr, and when, upon the trial of an adulterous woman, Jesus declares: “Let him who is without sin cast the first stone”

Let us, then, press on past this duality. Let us not start by confusing discovery and conquest, which was the point of Daniel Boorstin‘s book about scientific disclosure, The Discoverers (whose subtitle in the French translation by Robert Laffont [1989] is From Herodotus to Copernicus—From Christopher Columbus to Einstein—The Adventures of the Men who invented the World). Which means, of course, that these masters of the Voyage and these masters of Knowledge are one and the same. At the end of chapter 26, An Empire without Wants Boorstin writes: „Fully equipped with the technology, the intelligence, and the national resources to become discoverers, the Chinese doomed themselves to be the discovered.“

When Chinese alchemists during the tang dynasty searched for a potion for immortality (as is the philosopher‘s stone) they accidentally created the explosive mix that is gunpowder. It served medical purposes and made fireworks for centuries before it‘s military use.

Apart from fireworks, artist Ed Ruscha seems to be the only person who found good use to gunpowder, as he incorporated it as material in the late 1960s, diluting small canisters of it into water to achieve the smoothest possible gray texture on paper, and with such gray to write words such as: self, sin, eye, flaw, dusty, promise and vanish.

In 1969, Ed Ruscha became frustrated with the standard materials he used in his paintings and drawings. “I was concerned with the concept of staining something,” the artist explained, “rather than applying a film or coat or skin of paint on a canvas.” As alternatives to oil paint, Ruscha began to work with an inventive and often surprising range of organic materials, including axle grease, egg yolk, and blueberry extract. His experimentation with unorthodox substances extended to works on paper, including Two Sheets Stained with Blood. This drawing features two unconventional artistic materials, blood—belonging to a friend of the artist—and gunpowder, which Ruscha used in dozens of drawings in the late 1960s and early 1970s. As is typical of much of the artist’s work, a disarming graphic simplicity accompanies a host of sophisticated formal and pictorial dynamics. In a self-referential nod to his medium, paper is depicted on paper, and the two sheets appear to hover weightlessly—yet cast substantive shadows.

If you hold a stone long enough it becomes a weapon. That’s not how the song goes but in 1971 Caetano Veloso wrote the song If You Hold A Stone in homage to Lygia Clark’s artwork Stone & Air. It’s one of her famous relational-objects, from 1966. This was the height of the brazilian dictatorship, and the air was heavy.

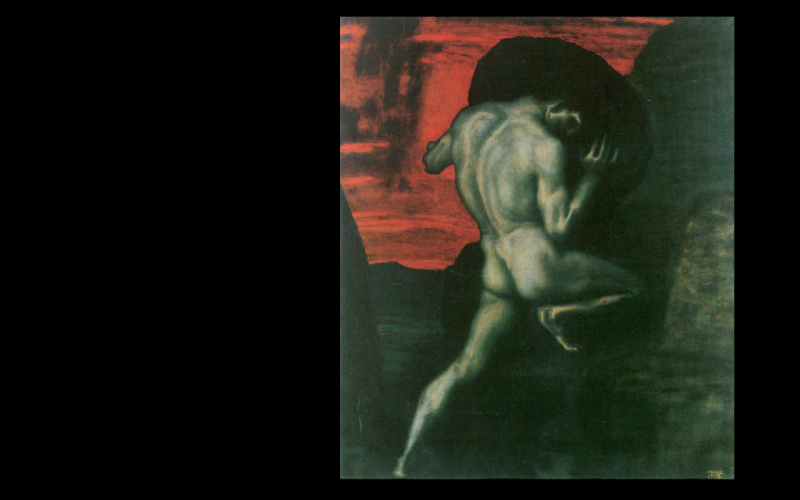

On timing to hold a stone, legend has it that Camille Claudel, forcefully kept in a sanatorium, would collect stones in the garden during the day, and in the evening ask the nurses to take the stones with them as they left, scattering them along the way, to set them free. Camille was kept in this facility from 1913 to 1943, the last 30 years of her life, inspite of the doctors claiming the lack of necessity, and inspite of her on will. Everyday, 30 years, handling stones in and out. One must imagine Sysiphus happy.

In 1902, Camille had casted the Medusa.

Two years before that, in 1941, Virginia Woolf packed her pockets with stones and jumped in the river ouse. In the previous year, her London home had been destroyed by German bombs, and she went back only to save some notebooks and journals from the ruins. Woolf published Orlando in 1928. Orlando cuts through the centuries and lives 400 years, in a tale of transformation and freedom. The Medusa is also transformed, though through punishment, and lives with her snake hair and turns anyone around her into stone.

Alice Rohrwacher made a film about a head of stone that gets lost. Digging the earth to find treasures, the archeologist-protagonist keeps the past for himself.

Alice says: “When I was little, I was learning that civilisations always come to an end. It makes me think ours will end, too. And that makes me wonder what we’ll leave behind.“

Final considerations: In opposition to stone, Anne Carson says of poems:

„I think a poem, when it works, is an action of the mind captured on a page, and the reader, when he engages it, has to enter into that action. And so his mind repeats that action and travels again through the action, but it is a movement of yourself through a thought, through an activity of thinking, so by the time you get to the end you’re different than you were at the beginning and you feel that difference. To speak of stillness, to speak of movement.“

In agreement with stone, again in 1966, the brazilian poet João Cabral de Melo Neto publishes the poem Education Through Stone, in the book The River. It ends with:

„In the barren land stone does not know how to lecture, and, even if it did would teach nothing: You don’t learn the stone, there: there, the stone, born stone, penetrates the soul.“

Unknowingly, in 1967, the Polish poet Wislawa Szymborska also wrote about the stone’s didactic refusal, published in the book Tables, the poem Conversation with the Stone, a slice:

I knock at the stone’s front door.“

It’s only me, let me come in.

I don’t seek refuge for eternity.

I’m not unhappy.

I’m not homeless.

My world is worth returning to.

I’ll enter and exit empty-handed.

And my proof I was therewill be only words,

which no one will believe.”

“You shall not enter,” says the stone.“

You lack the sense of taking part.

No other sense can make up

for your missing sense of taking part.

Even sight heightened to become all-seeing

will do you no good without a sense of taking part.

You shall not enter, you have only a sense

of what that sense should be,

only its seed, imagination.”

I knock at the stone’s front door.

“It’s only me, let me come in.

I haven’t got two thousand centuries,

so let me come under your roof.”

“If you don’t believe me,” says the stone,“

just ask the leaf, it will tell you the same.

Ask a drop of water, it will say what the leaf has said.

And, finally, ask a hair from your own head.

I am bursting from laughter, yes, laughter, vast laughter,

although I don’t know how to laugh.”

I knock at the stone’s front door.“It’s only me, let me come in.

“I don’t have a door,” says the stone.

Júlia Maria Moreira is a Brasilian artist, currently finishing her studies at HFBK Hamburg. "Corpo-Pedras" and other writings have already been brought to life many times as lecture-performances – besides many other activities an inherent part of Julia's artistic practice.

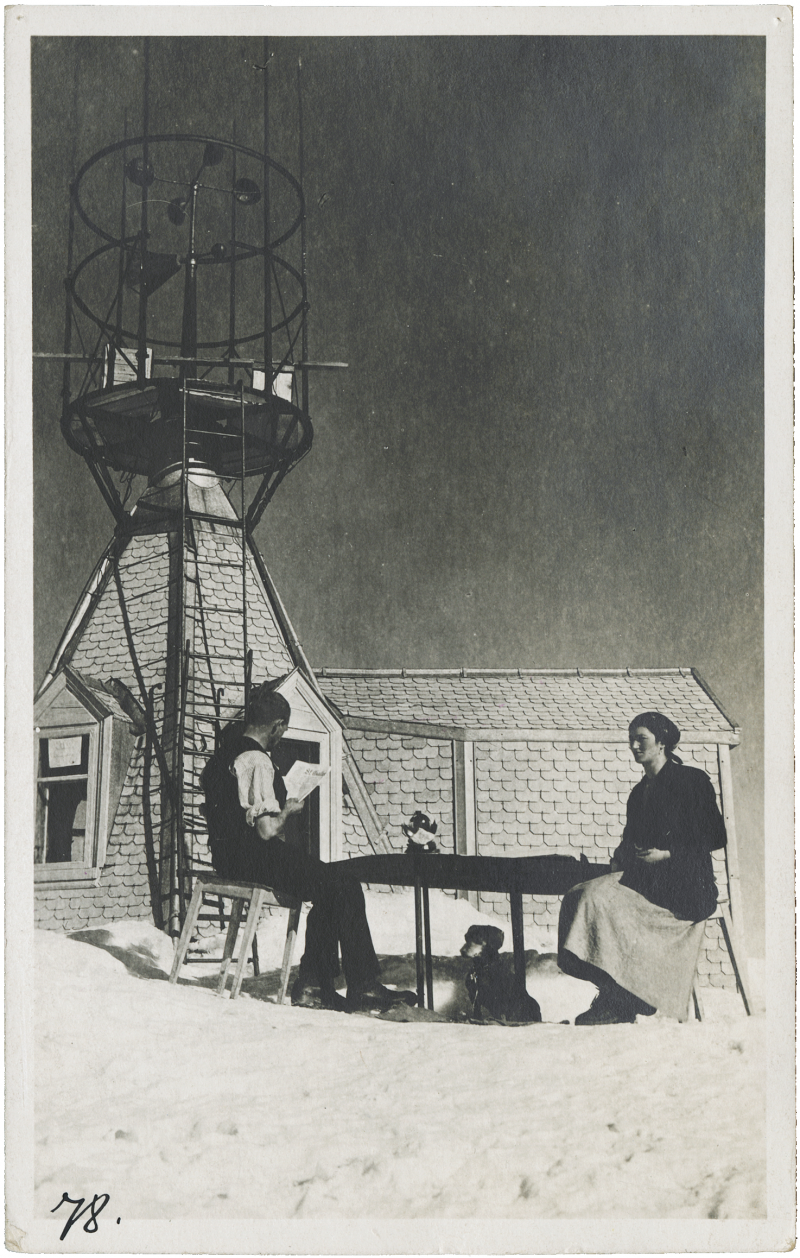

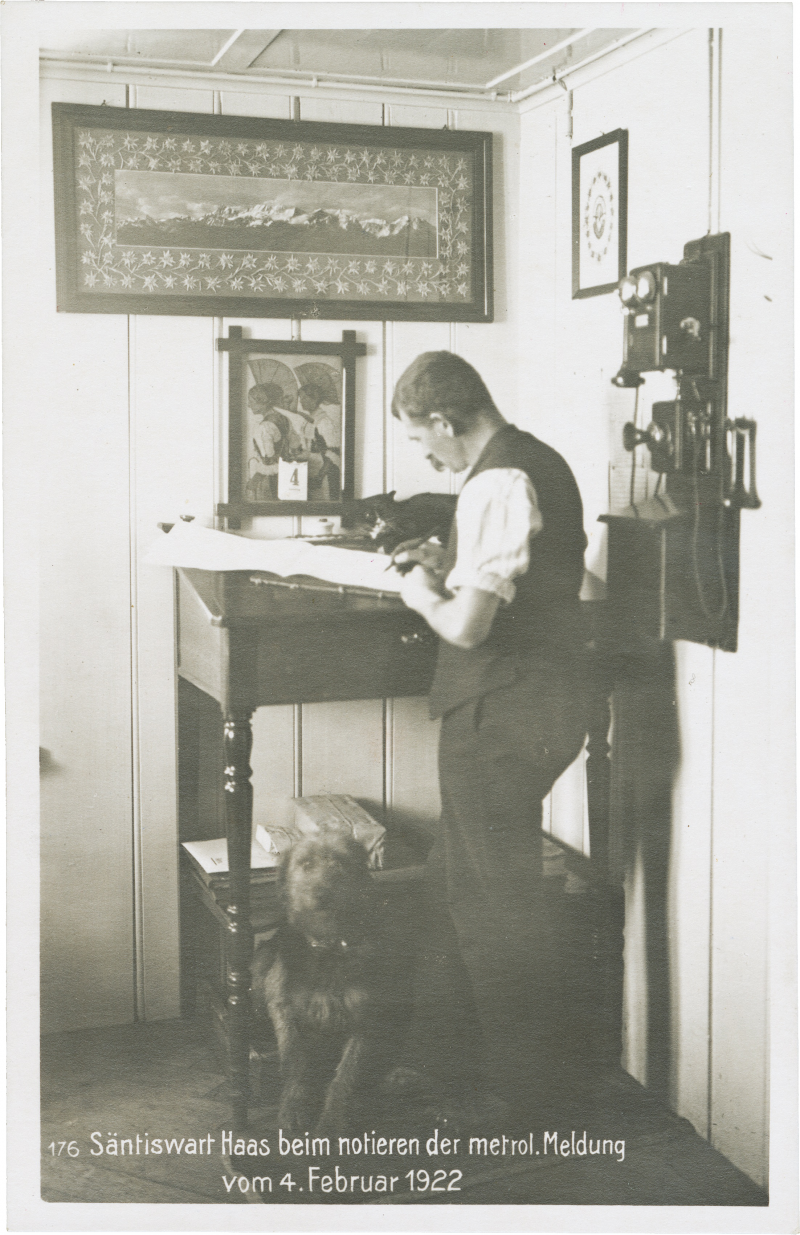

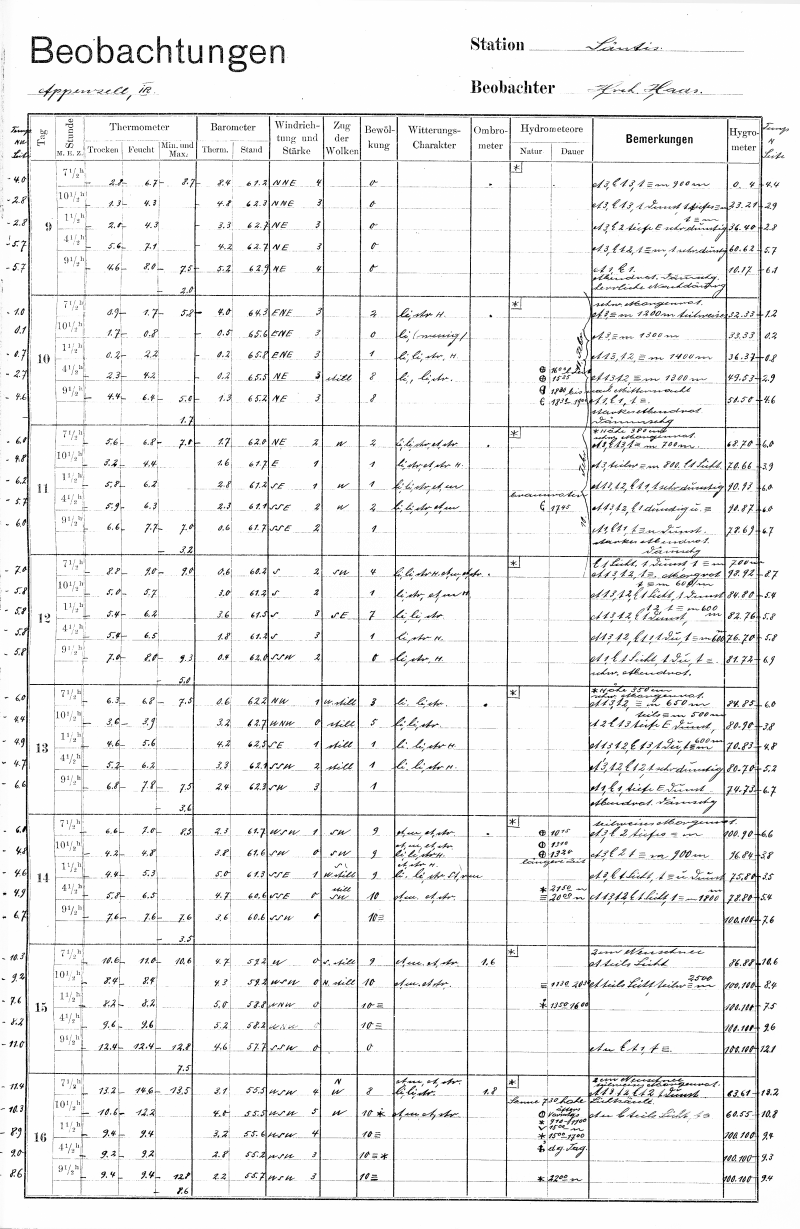

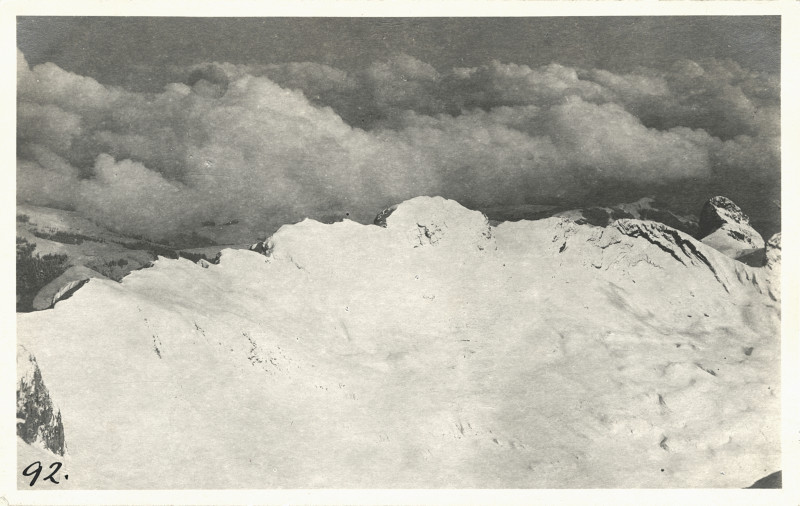

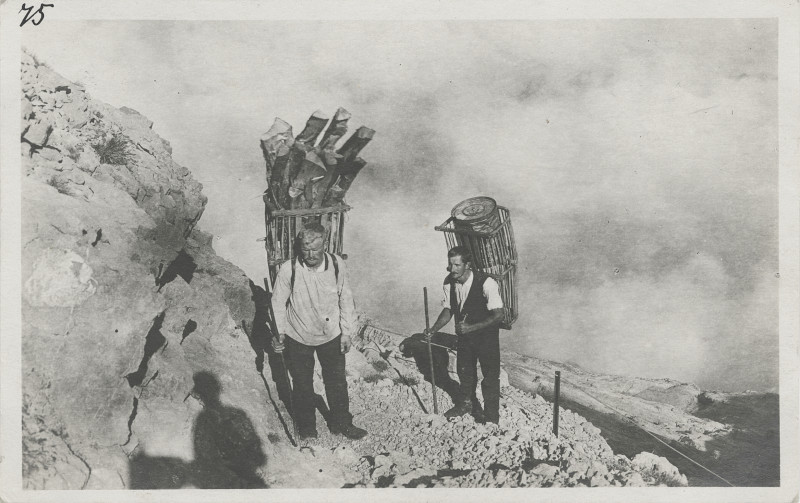

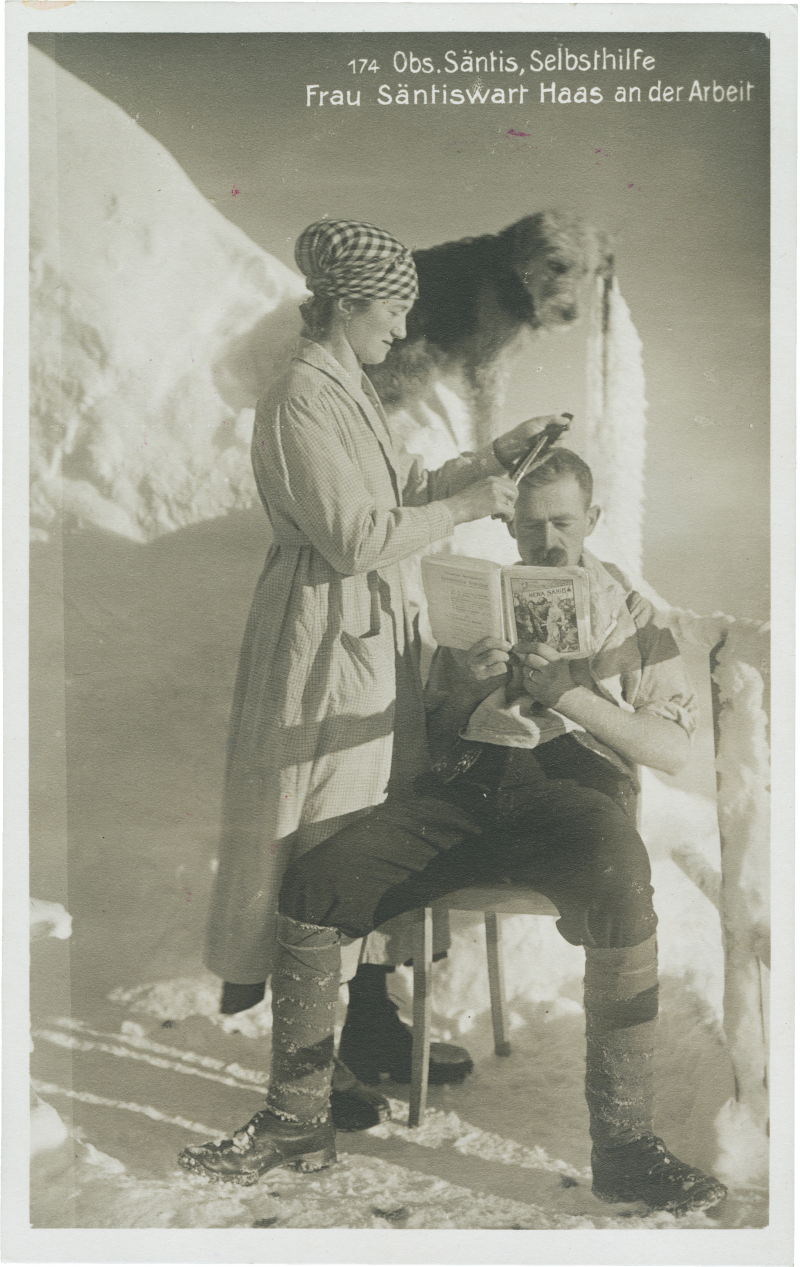

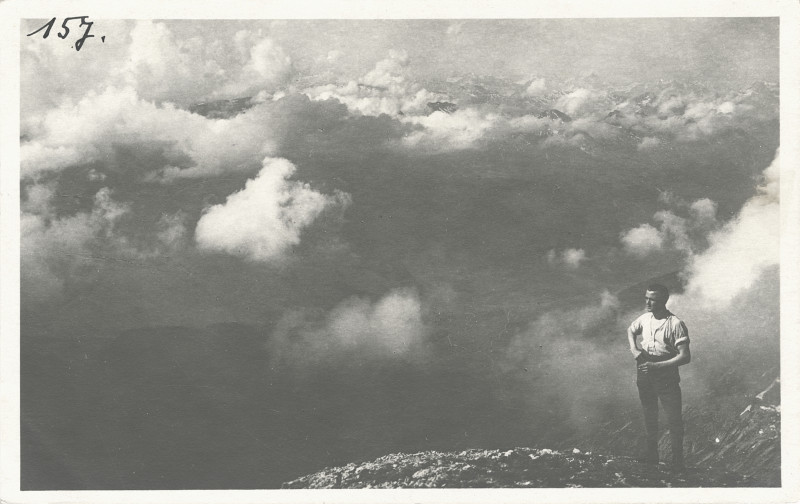

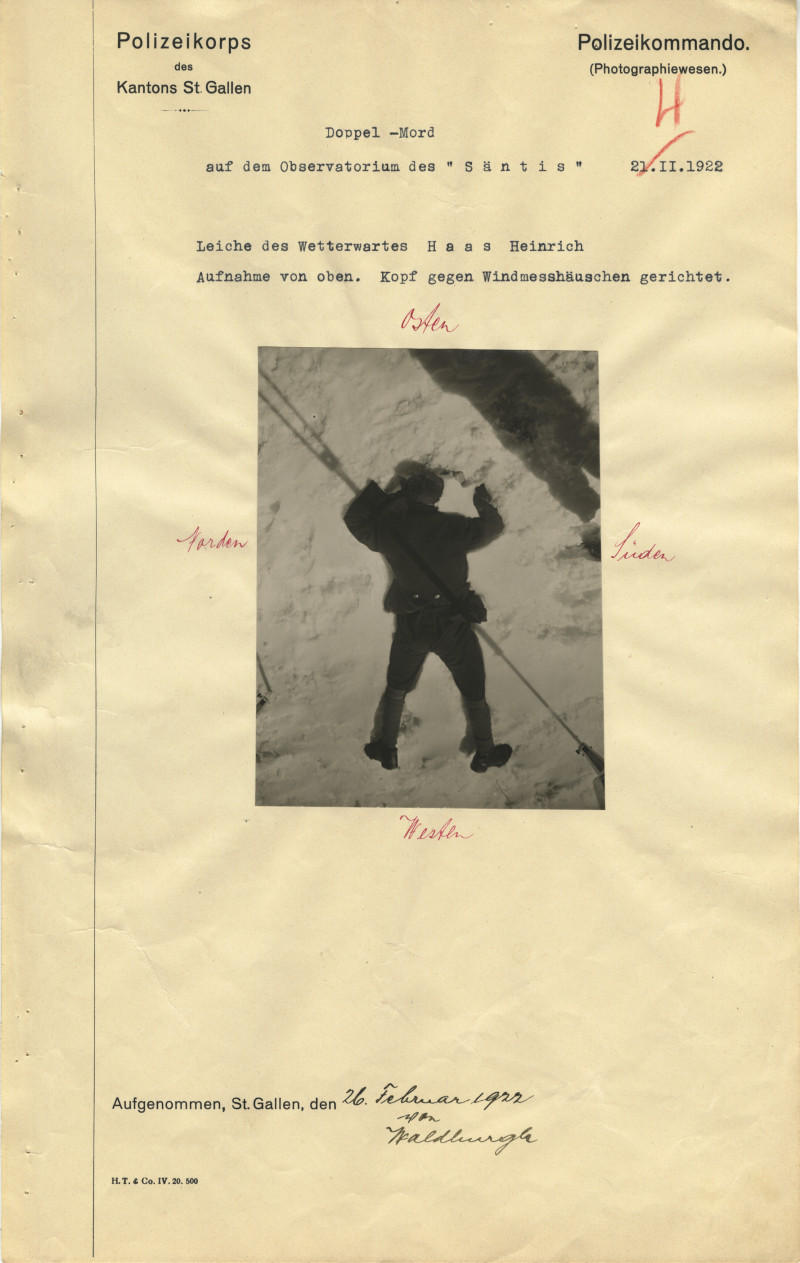

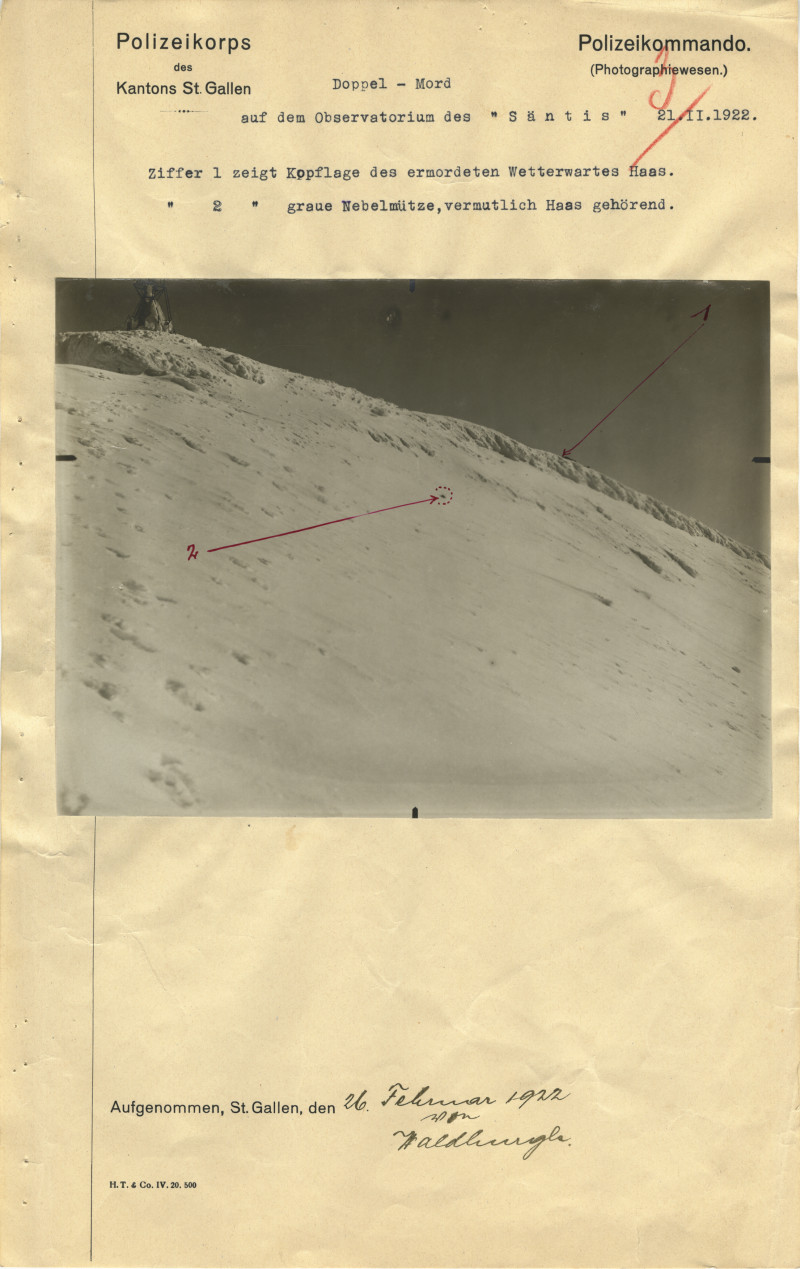

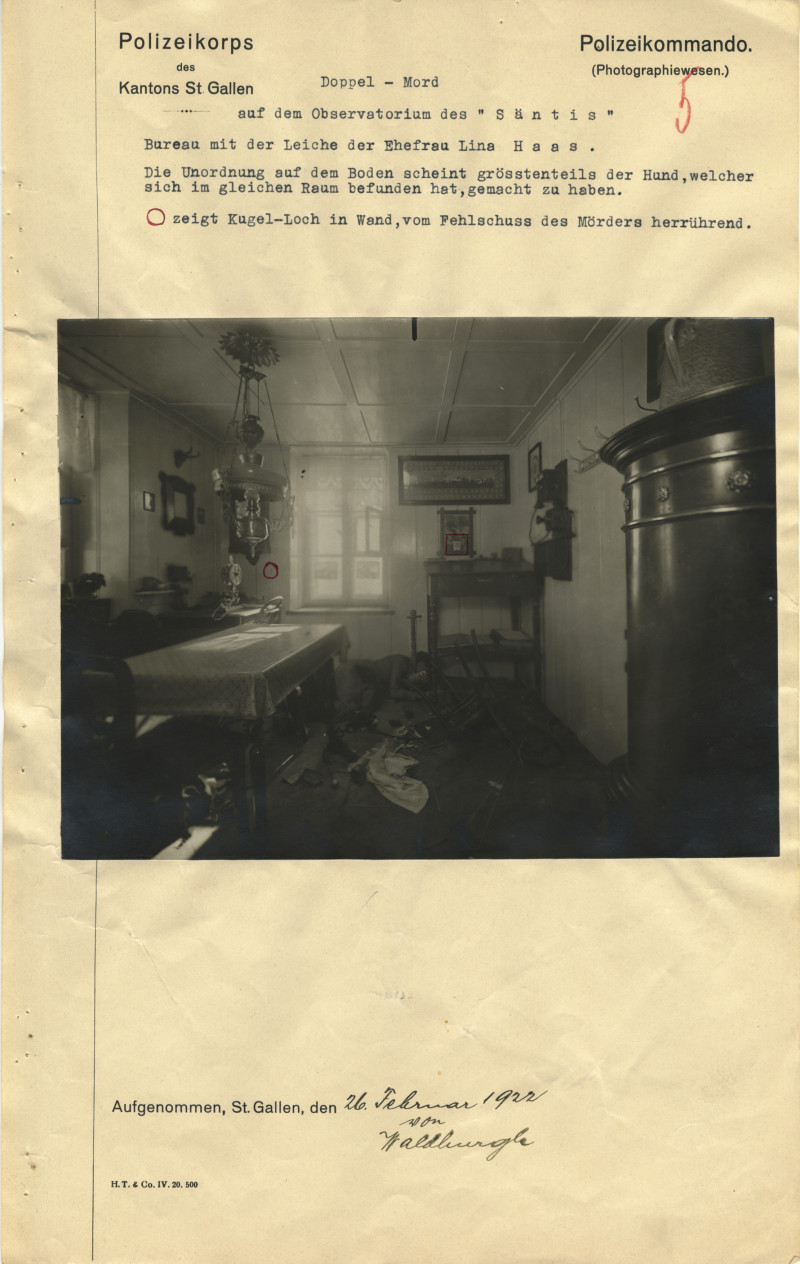

Atop the Säntis mountain, 3,000 meters above sea level, the married couple Heinrich and Magdalena Haas lived and worked in a small weather station. Every day, they transmitted their weather observations via telegraph down into the valley—until one day, the line went silent. Magdalena Haas was found in the devastated kitchen; Heinrich Haas was discovered farther down the slope, lying face-down in the snow. A rival had brought their shared life to an end. Archival photographs offer a glimpse into the intimate atmosphere of their togetherness—a sparse life framed by immense geological beauty.

Eliane Kölbener (born 1994) is a Swiss artist, currently studying at the HFBK Hamburg. In her work, she sheds light on the archives of her home town of Appenzell and examines data traces in an effort to reimagine their history.

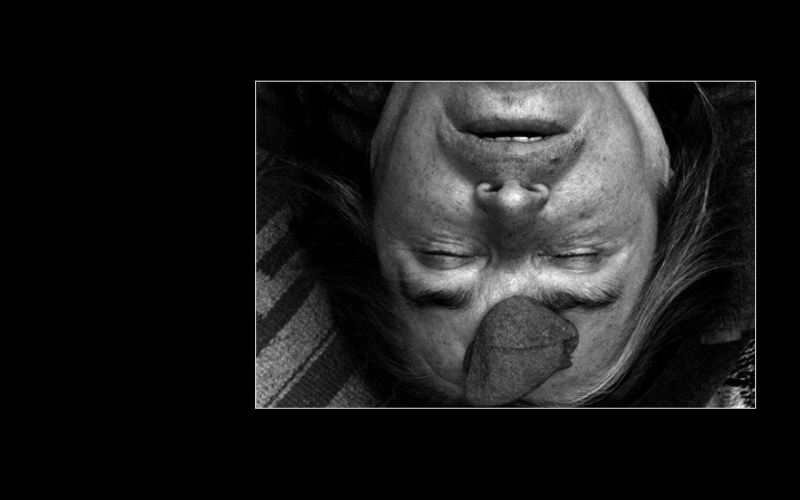

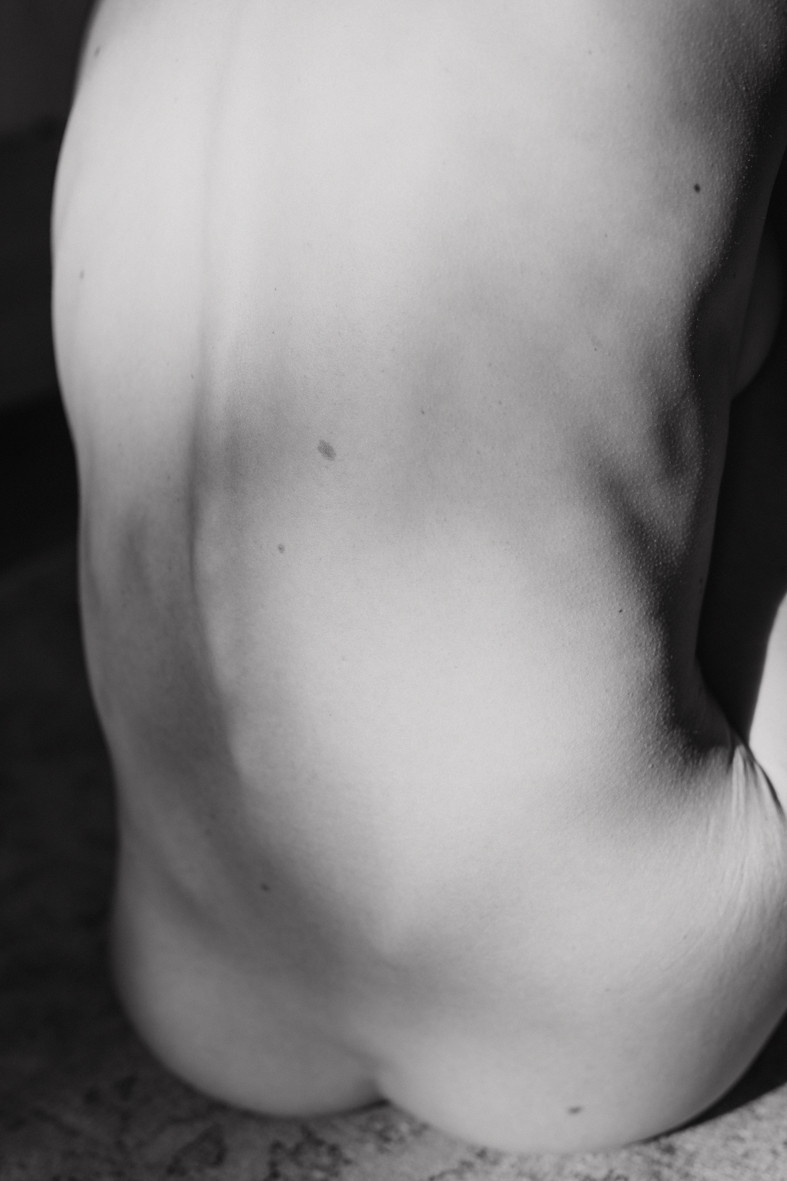

Teresa Pistorius (born 1991) is a German photographer, currently based in Lüneburg. In her serial works, she explores the human body, inner emotional states, and external perception in depth. Staged photography and self-portraiture serve as tools to capture intimate and sensitive moments. A central aim is to create visibility and to foster a sense of closeness and open, unprejudiced exchange between the portrayed, the viewer and their surroundings.

Digging deep and exposing,

extracting, but protecting.

⚘⚘⚘

A piece of advice on how to make the perfect sourdough by a baker, lends itselfas a metaphor to my alchemic approach and gives an idea of my relationship withmaterials: “The key to rising a well-adjusted starter is to observe its needs, give it spaceto grow and adjust the refreshments to encourage maximum fermentation activity.”

(Maurizio Leo)

Maj Mücke (born 1992) is a German artist, currently studying Fine Arts at the National Art School in Sydney. Her practice explores a non-representational aesthetic and a mode of excavation — one of rupture, rawness, preservation, and decay. Her works are composed of degradable materials and often include elements of malleable or natural matter.